Calf management

Calf management in dairy farm

The first 24 hours after a calf is born can have tremendous effects on their overall performance and health throughout their life. Calf management and rearing practices a key component of raising a healthy, productive animal. Explore best practices for colostrum management, navel dipping and other essential parts of your calf’s first day of life here. 66 % of calves that die in the perinatal period – the time immediately before or immediately after birth – were alive at the start of calving. Essentials for Calf management are:

The First 24 hours

- Calving management

- Delivery is a high-risk time for both the calf and the cow. Each need special attention, even after a smooth delivery. If there are problems during delivery even more attentive care is needed to help the cow and calf recover. Great calving management sets the dam up for a productive lactation and successful re-breeding, and the calf can start life on the right track.

- Maternity pens

- The maternity area should be in a quiet part of the barn. A maternity pen should be a minimum of 3 m x 3 m (10’x10′), and must be clean, dry, draft-free, and well lighted, insulated and ventilated. This will help with disease control, comfort and footing.

- Navel care

- Bacteria enter a calf’s circulatory system by way of the navel into the liver, and then into the bloodstream.

- Biosecurity

- The calf’s digestive system

- Colostrum

Calf nutritional development First day

Colostrum, which is the first milk that calves should take as soon as they are born (within the first 1 hour), is an extremely complicated secretion that is milked in the udder of the cow that gives birth with the birth. In the first 1 hour from birth and within the first 6 hours, 5% of the animal weight should be given 2 times, approximately 2-2.5 liters each time.

Important management issues and points to be considered while feeding the calf

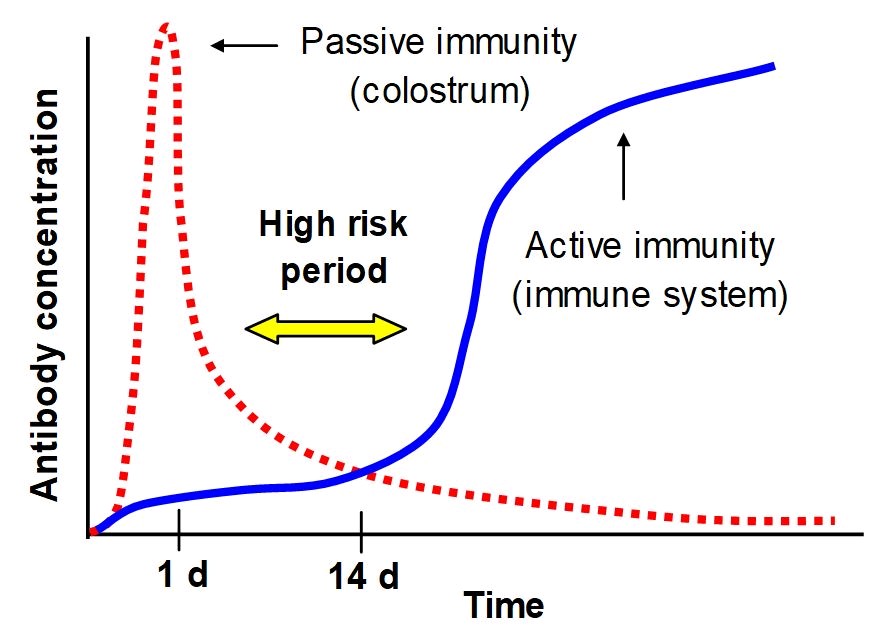

Calves are born with almost no immunity to diseases and very hungry. Since calves are exposed to stress as soon as they are born and are vulnerable to disease-causing factors, they urgently need quality colostrum. On the other hand, effective absorption of immune substances (IgG) from the intestine and mixing into the blood can only occur within the first few hours after birth. As time passes after birth, the concentration of IgG in colostrum and its absorption from the calf intestine decrease rapidly, and at the end of the 24th hour, the absorption decreases to 10%.

Colostrum for calf nutrition and development contains 2 solids of dry matter, 3 times of mineral and 5 times of protein compared to normal milk; It has vitamins, energy, growth factors, hormones and immune substances (IgG) that help the calf to protect it from diseases. Quality colostrum is the only elixir of wellness for the calf.

Nourish the calves

Providing pre-weaned calves with a rich diet provides many benefits to the animal, the environment, and farm profitability. The first 12 weeks of a calf’s life has a big influence on her health, how quickly and efficiently she can be bred, how much milk she will eventually make, and even influences how many lactations she will have. These factors are the driving characteristics of how profitable this cow will be. To set your calf up for sustainable and profitable lifetime performance, you can focus on these 5 critical control points which effects calf life needs calf management system

- Colostrum: Calves need to receive 3 to 4 liters of high-quality colostrum as soon after birth as possible, preferably within the first hour of life. An additional 2 liters within the first 6 hours and another 1 to 2 liters within the first 12 hours is recommended to fortify the calf’s immune system.

- Calories: Provide calves with a rich diet for optimal immunity, growth, and future performance. Intensive feeding of a highly digestible calf milk replacer for the first 8 weeks of life followed by a stepdown weaning period of 2 to 4 weeks will deliver the plane of nutrition required to optimize performance.

- Consistency: Consistent feeding and cleaning schedules will improve calf performance, health, and welfare. Provide a high quality and consistent source of water, milk replacer, grain, and forage.

Housing Calves

- Cleanliness: Keep the calving area and calf housing area clean and dry. Feeding equipment must be maintained with proper hygiene protocols.

- Cleaning calf housing is one of the best things we can do to keep calves healthy. Considering the fragile nature of a newborn calf’s immune system and that many calf sicknesses are a result of contagious diseases; it is hard to justify skimping on cleaning and disinfection.

- Comfort: Calves should be housed in a dry, bright, and well-ventilated environment with soft bedding.

- Calves housed individually can be easier to monitor than pair or group-housed calves, but individual housing does not reduce the risk of disease transmission among calves. Calves are a social animal, so pair or group housing allows them to express normal social behavior and fulfill their need for social contact. Current research recommends housing calves in small, well-managed groups from arrival onto the farm. Pair housing allows for close monitoring of calves while providing social stimulation.

- Group Managing pre-weaned calves in group housing is different than managing young calves in individual pens or hutches. Assessing things like the amount of milk, water or solid feed consumed, or manure passed is much simpler when calves are housed individually, however some auto-feeders do monitor milk intake. Despite this, producers can successfully raise healthy and well-grown calves efficiently in groups from a young age.

- Ventilation good air quality leads to healthy animals and a productive animal facility. The goal of ventilation is to provide adequate fresh air that is free from dust and drafts. The air should be reasonably free from pollutants such as ammonia, carbon dioxide and air–borne pathogens. Moisture accumulates and humidity rises when animals are confined without adequate ventilation, so proper air distribution is essential. In totally enclosed buildings, the preferred relative humidity range is 55 – 75 per cent.

Warm weather don’t forget that calves can also experience stress when the temperatures start to rise. When it is over 25 °C, calves may need special attention to keep cool, healthy, and productive. Calves are at their best in environments between 12 – 25 °C. Once it gets warmer than that, they’re eating less and using energy trying to keep cool instead of devoting that energy to growth.

Heat stress

Hot and humid weather can take its toll on people, but calves are also susceptible to heat stress. To ensure calves stay healthy and maintain their growth rates, it’s important to keep them cool and comfortable during the sticky summer months. Calves are at their best in environments between 12 – 25 degrees Celsius. Once it gets warmer than that, they’re eating less and using energy trying to keep cool instead of devoting that energy to growth.

Hot and humid weather can take its toll on people, but calves are also susceptible to heat stress. To ensure calves stay healthy and maintain their growth rates, it’s important to keep them cool and comfortable during the sticky summer months.

Calves suffering from heat stress will show signs of reduced movement, decreased feed intake, higher water consumption, rapid respiration, open-mouth breathing and a lack of co-ordination in their movement.

Cold stress

The thermoneutral zone is the temperature range where calves don’t need any additional energy to maintain their body temperature. From birth until four weeks of age, this range is between 10°C and 25°C (50 – 77°F), and from four weeks to weaning, it increases to 0°C to 25°C (32 – 77°F). This means that if temperatures are outside of these ranges, calves need extra nutrition to keep warm and healthy.

When temperatures fall below 15°C, calves less than three weeks will start to use energy to keep warm. Calves older than three weeks start to use energy to keep warm when the temperature is below 5°C. This means if producers do not offer calves more milk (energy), the milk calves are given will be used to keep warm instead of for growing or protecting against disease. Calves not given enough feed in cold weather will not grow and may even go backward and lose weight.

Calf management Tips

Signs your calves might be suffering from cold stress:

- They’re shivering, breathing rapidly, or have raised hair.

- Their hooves or muzzles are excessively cold and losing color – the body could be diverting blood from the extremities.

- They’re showing a decrease in body temperature.

Feeding in cold

- When temperatures fall below 15°C, calves less than three weeks will start to use energy to keep warm. Calves older than three weeks start to use energy to keep warm when the temperature is below 5°C.

- This means if producers do not offer calves more milk (energy), the milk calves are given will be used to keep warm instead of for growing or protecting against disease. Calves not given enough feed in cold weather will not grow and may even go backward and lose weight.

- Feeding more milk in winter is recommended but increasing milk won’t make up for wet or shallow bedding in the winter conditions.

- A good rule of thumb is to increase the amount of milk replacer by 2% for every degree the temperature falls below 5°C. When the outside temperature is 5°C, 4 liters/day at a concentration of 125g/l is starvation for a calf.

- Introduce changes to a calf’s feeding program gradually and carefully. If you’re feeding more milk, provide it as an extra meal or two instead of increasing the size of the meals you’re already feeding.

- Feed milk at a warm temperature (38.5°C); otherwise, the calf uses its own energy stores to warm the milk to body temperature.

Calf Housing in cold

- Ensure calves have enough bedding to keep them dry and warm. During the fall, winter and spring months, ensure you are bedding with straw, which will help to reduce a calf’s heat loss. Straw should be at least 8 cm (three inches) deep, and dry.

- To determine if a calf has enough straw, do the “kneel test”: kneel on the bedding for 20 seconds and if your knees get wet, change the bedding or add to it.

- Dry off newborn calves and use heat lamps to keep them warm. Wet hair cannot insulate the calf, and as the water evaporates, it takes heat with it and is extremely energy‐costly in young calves. Follow other good winter management practices such as blanketing, providing enough straw for nesting, and making sure calves have free access to warm water.

- Straw is more absorbent than shavings, which helps keeps calves dry. A wet calf is a cold calf. Keeping calves warm reduces the incidence of respiratory disease, and straw is the warmest bedding type (compared to alternatives such as shavings, sand, rice hulls, or non-organic options)

- Deep straw bedding allows a calf to nest and trap warm air around their body. When calves are laying down, you shouldn’t be able to see their legs. Usually 3-4 inches (7.6-10 centimeters (cm)) of shavings topped with 12 inches (30 cm) of straw is ideal.

- Add bedding often instead of adding large amounts all at once. This will keep the top layer fluffy (rather than compacted) and dry.

Feeding Calves

Sucking behavior of dairy calves

Fed milk ad libitum by bucket or teat: The milk intake and sucking behaviour of Dutch and Holstein-Friesian crossbred calves fed milk replacer ad libitum by either the bucket method (n=8) or an artificial teat (n=6) were compared. The animals were observed for 3 weeks from the age of 2 weeks, penned individually and all provided with a “dummy” (artificial) teat near the milk source within the pen.

The teat-fed calves ingested significantly more milk than the bucket-fed calves (11.9 vs. 8.0 kg/day; P<0.05), and this intake took much longer (44.2 vs. 17.7 min/day; P<0.05). In both treatment groups, milk intake was organized in “meals”. The meal criterion, separating the within meal and between-meal non-feeding intervals, was set at 5 min. Frequency of meals and daily total meal duration did not differ significantly. Meals occurred rather randomly throughout a 24-h period.

On average, the dummy teat was used for 13 min per day by bucket-fed calves, but for only 1 min by teat-fed calves (P<0.05). Sucking of the dummy teat was largely clustered within the meal periods.

It is concluded that in the young calf a need for sucking exists independently of milk satiation. However, the level of satiation depends on whether the calf drinks or sucks the milk. Nutritive sucking is clearly more reinforcing than non-nutritive sucking. https://www.sciencedirect.com

The calf’s digestive system

- Water is the most essential and cheapest ingredient in any livestock feeding operation. A 180–kg calf will require from 10–30 liters of water daily, depending on factors like temperature, humidity and the dry matter content of the diet. To achieve maximum gains, provide an adequate supply of clean, easily accessible water. Test the water offered to calves and mixed with milk replacers as the pH, mineral content and bacterial counts are of primary concern. It may be necessary to install water treatment equipment to ensure good water quality for your animals.

- Feeding calves milk through a nipple instead of an open bucket provides advantages for their digestive physiology, health, productivity, and welfare. Allowing bucket-fed calves to suck from dry a nipple after feeding provides some of these advantages

- Milk feeding

- Automatic feeders

- Solid feeding

- Cold weather feeding

- Hot Weather Feeding

- Weaning or transitioning a calf from a milk-based to a solid feed diet, is most stressful times in a calf’s life. Implementing management strategies such as gradual weaning, group housing, and providing access to starter and water is essential for improving the overall health, welfare and economical potential of the calves. Find helpful advice for making this transition easier for your calves here for better calf management.

Sucking behavior of dairy calves

Fed milk ad libitum by bucket or teat? The milk intake and sucking behaviour of Dutch and Holstein-Friesian crossbred calves fed milk replacer ad libitum by either the bucket method (n=8) or an artificial teat (n=6) were compared. The animals were observed for 3 weeks from the age of 2 weeks, penned individually and all provided with a “dummy” (artificial) teat near the milk source within the pen.

The teat-fed calves ingested significantly more milk than the bucket-fed calves (11.9 vs. 8.0 kg/day; P<0.05), and this intake took much longer (44.2 vs. 17.7 min/day; P<0.05). In both treatment groups, milk intake was organized in “meals”. The meal criterion, separating the withinmeal and between-meal non-feeding intervals, was set at 5 min. Frequency of meals and daily total meal duration did not differ significantly. Meals occurred rather randomly throughout a 24-h period.

On average, the dummy teat was used for 13 min per day by bucket-fed calves, but for only 1 min by teat-fed calves (P<0.05). Sucking of the dummy teat was largely clustered within the meal periods.

It is concluded that in the young calf a need for sucking exists independently of milk satiation. However, the level of satiation depends on whether the calf drinks or sucks the milk. Nutritive sucking is clearly more reinforcing than non-nutritive sucking. https://www.sciencedirect.com

Health and welfare

- Calf-hood diseases

- Pneumonia

- Scours

- Dehydration

- Treatment and prevention

- Medications

- Why are calves so vulnerable to illness?

- Early disease detection

- Cleaning

- Biosecurity

- Euthanasia

- Disbudding and dehorning

- Important tips to improve calf comfort during castration

- Veterinariation